Reviewed by Priscilla Issa

There is something infrequently discussed and yet often felt in performing arts circles - the mental and emotional struggle an artist experiences when they compare their talent against the talent of others. Artists yearn for unrivaled talent; the slightest semblance of prodigiousness justifies egocentrism. Yet, there is something so humbling (and for some, devastatingly painful) in the realisation that one’s talent in fact operates in a grander sphere of mediocrity. There is always that one other person who does it just that little bit better. Individuals wrangle with this struggle in a plethora of ways. Some artists retreat into the background; their self-confidence is shattered. Others are ruthless, destroying relationships on their way to the top. There is, of course, the age-old saying “fake it til you make it”, which some people swear by. Then there’s the individual that blames external forces, like God, when things don’t go their way.

This last theme was explored in Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin’s 1830 story, Mozart and Salieri, which tells of the supposed 18th Century rivalry between Classical composers, Mozart and Salieri. Basing his play on the original, Peter Shaffer’s play, Amadeus (1979), looks at Salieri’s eventual undoing when he discovers “boy genius”, Mozart, composing chamber music and concerti at seven years old. Where is the pact Salieri makes with God that he would be an unrivaled composer? The line that captures Salieri’s torture is “we were both ordinary men, he and I. Yet from the ordinary he created legends!” Salieri is convinced God has deserted him and that he favours Mozart. Australian theatre director, Crag Illot, bravely reimages Amadeus at the Sydney Opera House. This new production is both a ‘sensory fusion of theatre, art, fashion, and music’ and an opportunity for audiences to journey through what can only be described as the ugliest parts of an artist’s psyche.

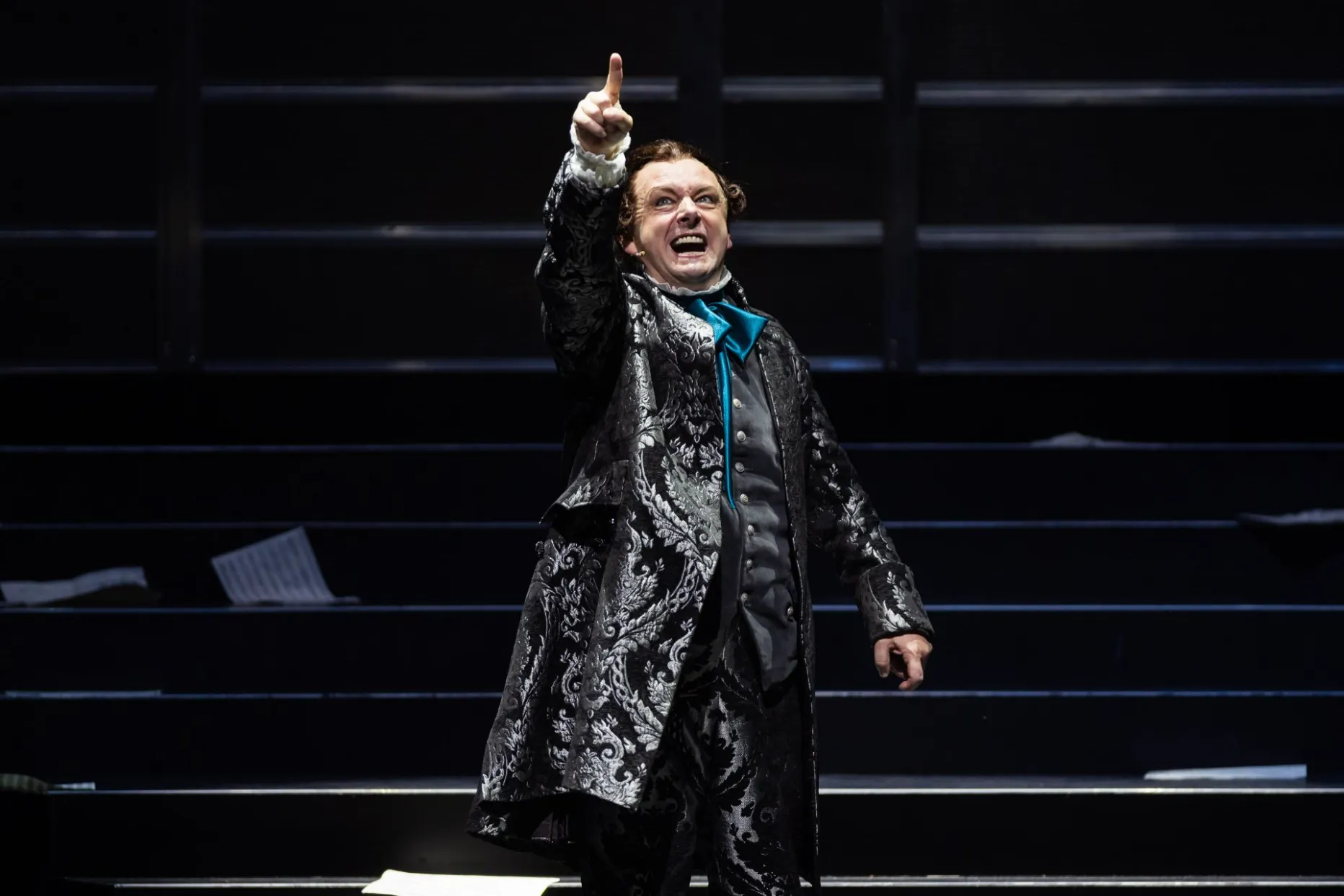

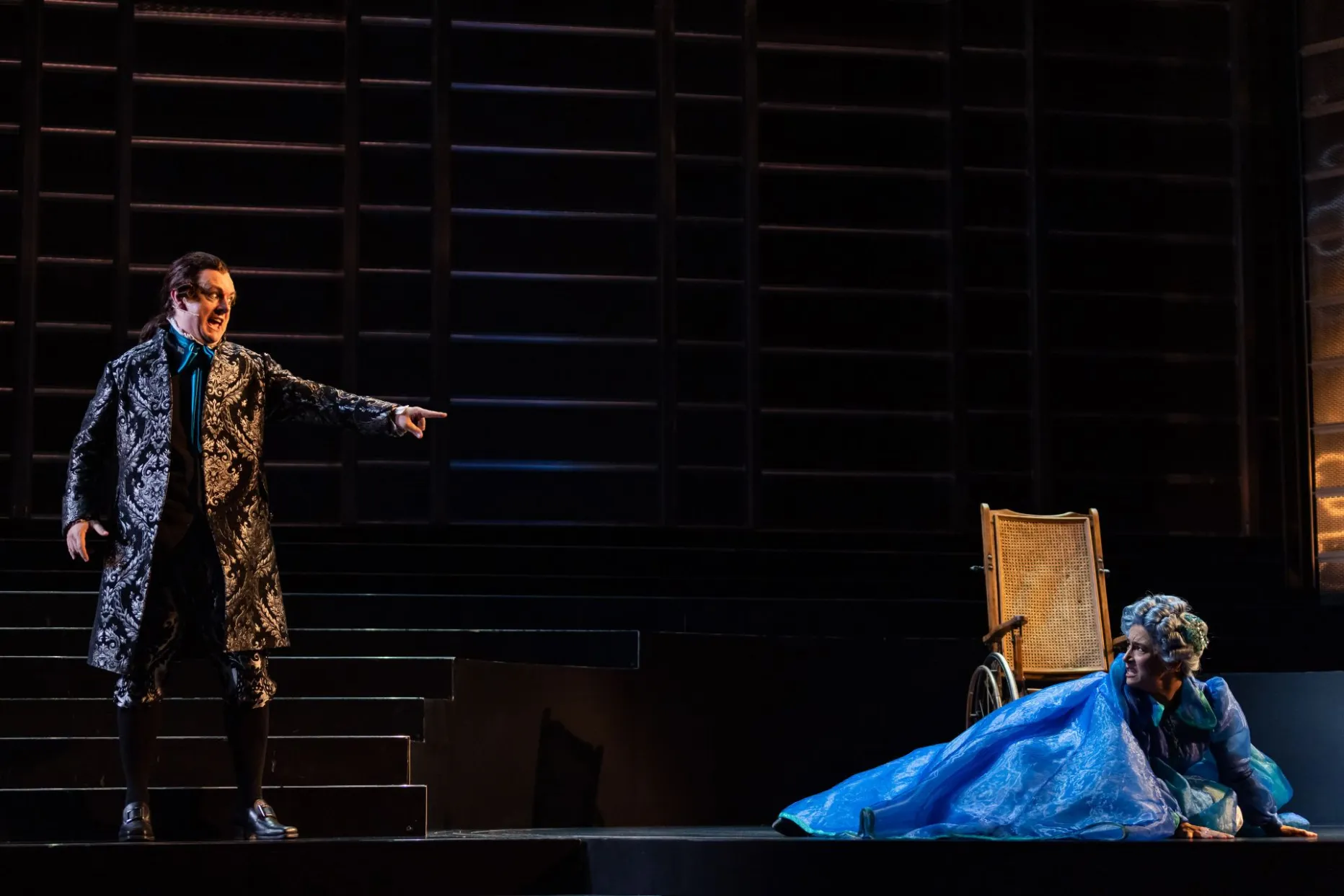

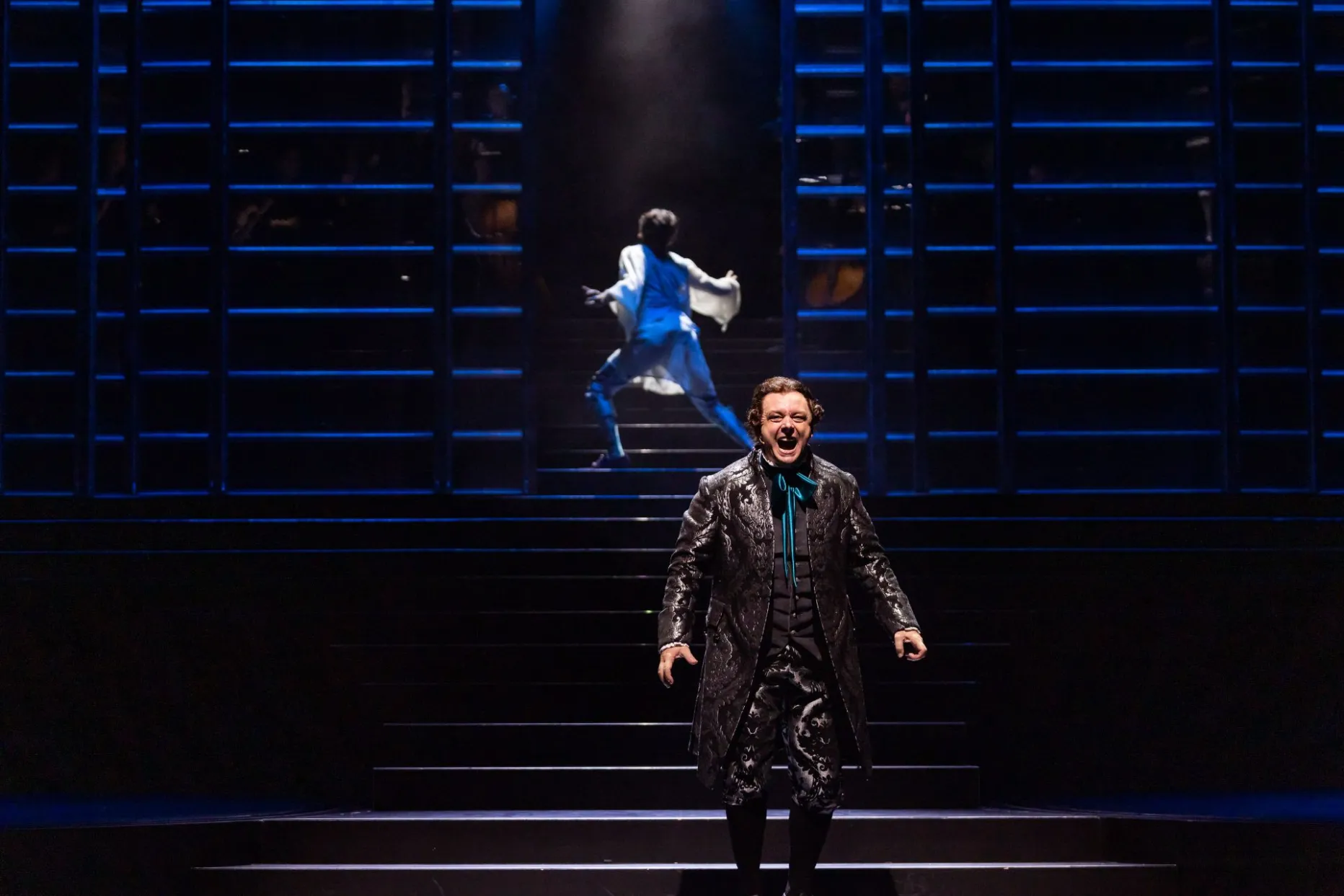

It should be noted that lead actor, Michael Sheen, is no stranger to Shaffer’s play. He played the infantile and likable Mozart at The Old Vic in 1998, which won him commendation in England and abroad. Arguably, Salieri is the more challenging of the two lead characters. It was high time the acclaimed and experienced Welsh actor attempted something of this magnitude. Sheen undeniably rose to the occasion, tackling the over two-hour broken-up soliloquy with maturity, adaptability, and sophistication. He impressively bounced between vengeful and tormented creative, pitiful and sympathetic colleague, and bitter, old cynic. Audiences witnessed a world-class performance of a man’s creative spirit crumbling as he grasped the enormity of Mozart’s talent and the limitations of his own. Sheen’s performance was also a lesson in vocal versatility. Tony David Cray’s sound design brilliantly amplified Sheen’s grumbling and growling, holding audiences in his thrall. The cherry on top was his impeccable comedic timing. In sum, this was a tour de force performance.

The child-like Mozart was played by Rahel Romahn. This performance held its own against the might of Sheen’s performance. Romahn captured the frivolity, whimsy, and fragile physicality of the character. History has it that Mozart fell into misfortune and ill health. In more serious scenes, Romanh’s portrayal of Mozart’s desperation and decaying mind was heartbreaking.

Looking at both performances side by side, audiences can clearly see the parallels in artistic turmoil. It’s like the characters convey two sides of the same coin. One man’s self-esteem dissipates despite his growing fortunes. The other’s fortune is lost, despite his grandiose self-perception. In the end, one lives and the other dies, in darkness. Interestingly, both have made it to 'legendary' status in their own way - one in fame and the other in infamy.

Lily Balatincz played Constanze, Mozart’s initially juvenile and free-spirit wife. In the second half, her portrayal of a mature and forward-thinking wife, highlight the nuances of Lily’s talent. A welcome reprieve from all the ‘woe is me’ theatrics is Toby Sschmidt’s comical and cartoonish performance as Emperor Joseph II, whose perfectly timed quips help paint a picture of royals being so devoid of empathy and removed from reality. Salieri’s spies, the two Venticelli, are played by the formidable Belinda Giblin and Josh Quong Tart. Giblin and Quong Tart’s mannerisms and Baroque costumes scream of commedia dell’arte jesters. Yet, their drawn-out vocals give weight to the gravity of the themes. Their performance was the much-needed glue that held the melodramatic theatrics and realistic themes together.

Michael Scott-Mitchell’s set was perfect for the Concert Hall. It conveyed the grandeur of a royal court and the levels allowed for numerous creative choices in blocking. Nick Schleiper’s lighting filled the blank stage spaces and created intimacy in one-on-one dialogues, opulence in the opera scenes, and darkness in moments of quiet and solitude.

Of note were the ornate costumes designed by visionary Anna Cordingly, alongside Luke Sales and Anna Plunkett from fashion house Romance Was Born. Those sitting closest to the stage were fortunate enough to bask in the vibrance of the colours and the vividness of the print details.

It would be remiss not to mention the operatic vocal agility of Katherine Allen, Laura Scandizzo, Michaela Leisk, Daniel Vershuer, Daniel Macey and Joshua Oxley, and the glorious sounds of the Metropolitan Orchestra, conducted by Sarah-Grace Williams. Such ensemble awareness and beauty of sound!

The Concert Hall can prove an audacious choice for a play. But all things considered together, this production was an exhilarating way to start the Sydney Opera House’s 50th-year celebrations. Congratulations one and all!

Image Credit: Daniel Boud